BLOG

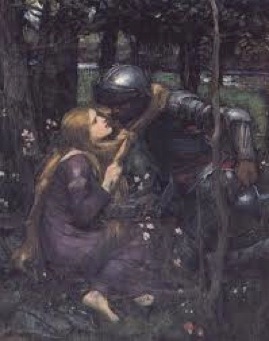

La Belle Dame Sans Merci

I just heard (on National Public Radio) an analysis of Hollywood romantic comedies that concluded people in these movies can’t have sex without falling in love . “Friends with benefits” doesn’t work, according to the movies.

Well in European mythology, and I’m talking anywhere from the Greeks through the Romantics, there are people out in the woods, usually women, but occasionally men, who are just looking for some no strings play . They’re called nymphs or faeries or maybe even elves. (That’s where the term “nymphomaniac” comes from.) If a human gets involved with one, he or she can look forward to a fun weekend, but a lifetime of remorse, heartbreak, or unwed motherhood after. In fact, the human can lose his or her soul! That’s what almost happened in The Holy Grail story to Sir Perceval when one of these loose women got him a little drunk. Sound too much like last weekend?

Allegorically, the faerie folk represent our natural desires. That’s why people always find them out in nature, especially in the woods, which, symbolically, represent situations in which one is morally lost. (Deep dark woods with no paths used to cover Europe.) Christian knights used to take vows to be good. They had a code of moral behavior to follow. So this story represents how our natural desires will generally triumph over both love and ethics, leaving us feeling like crap.

Friday, September 2, 2011

I.

O WHAT can ail thee, knight-at-arms,

Alone and palely loitering?

The sedge has wither’d from the lake,

And no birds sing.

II.

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms!

5

So haggard and so woe-begone?

The squirrel’s granary is full,

And the harvest’s done.

III.

I see a lily on thy brow

With anguish moist and fever dew,

10

And on thy cheeks a fading rose

Fast withereth too.

IV.

I met a lady in the meads,

Full beautiful—a faery’s child,

Her hair was long, her foot was light,

15

And her eyes were wild.

V.

I made a garland for her head,

And bracelets too, and fragrant zone;

She look’d at me as she did love,

And made sweet moan.

20

VI.

I set her on my pacing steed,

And nothing else saw all day long,

For sidelong would she bend, and sing

A faery’s song.

VII.

She found me roots of relish sweet,

25

And honey wild, and manna dew,

And sure in language strange she said—

“I love thee true.”

VIII

She took me to her elfin grot,

And there she wept, and sigh’d full sore,

30

And there I shut her wild wild eyes

With kisses four.

IX.

And there she lulled me asleep,

And there I dream’d—Ah! woe betide!

The latest dream I ever dream’d

35

On the cold hill’s side.

X.

I saw pale kings and princes too,

Pale warriors, death-pale were they all;

They cried—“La Belle Dame sans Merci

Hath thee in thrall!”

40

XI.

I saw their starved lips in the gloam,

With horrid warning gaped wide

And I awoke and found me here

On the cold hill’s side.

XII.

And this is why I sojourn here,

45

Alone and palely loitering,

Though the sedge is wither’d from the lake,

And no birds sing.

There are two speakers in the poem. The first person is wandering through the woods and finds a knight looking sad, worn out, and pale just sitting there. He or she asks the knight, “What’s a matter witch you, boy?”

Note that winter is coming. The seasons often represent the stages of one’s life. So this knight, who is pining for lost love, is approaching the age when he should be chill instead of long for a thrill. (Man, it’s the story of my life!)

Okay, if anybody tries to tell me this guy has flowers on his head, I’m going to have to punch him in the stomach with a bazooka! (That’s what I used to tell my classes.) Lilies, at least the metaphorical ones, are white, so the guy is pale, and sweating. His rosy cheeks are fading. He looks sick!

Now the knight is talking. He says he met a hot girl in a meadow. Wonder what’s going on with her foot? Well, women didn’t wear revealing clothes for much of European history. Although bosoms went in and out of fashion, it was especially rare to show any leg. So, a bare foot, which is attached to a hidden leg, is really sexy! Note that her hair is down, which signifies that she’s ready for action, and her eyes, the windows to her soul, are wild.

This is typical knightly wooing. Guys would make jewelry out of vines and flowers as they walked with their girls in the woods. (A zone is like a belt, in this usage.)

Of course, the couples would go out to the woods so they could find “...a fine, a private place...” to do some kissing, etc. (like ETC.!!!!!)

This sweet moan, and the faery song and “...language strange..” of the next verses, always kill me. He doesn’t understand her words, but he still gets the meaning.*

This isn’t sex, yet, you enthusiastic interpreters, but it’s foreshadowing. Nudge, nudge, wink, wink!

Don’t forget this! Eating is a sensual pleasure, so, in literature it’s sexy! Also, eating together is a form of communion, so they are becoming close. Shared experience is a big part of attraction, according to some studies I’ve read.

A “grot” is a grotto or cave. Note: she doesn’t have a house. She’s part of nature.

This whole weeping flirt has worked on me too often. Guys are putty when pretty girls cry.

He kisses her eyes! Guys remember that move, but be gentle!

Keats being a polite fellow, doesn’t describe the actual love-making, but after the steed and the moaning and the kissing we get the picture. She seduced him, and now, in a dream, all of her other one night stands come and tell him she has done it to them, too.

To be in thrall, is to be enslaved. So the “...beautiful woman without pity...” will seduce and abandon you, but you will forever after be her servant, and forever suffer. It’s a mistake, in this poem’s message, to think that sex means something spiritual or emotional. To La Belle Dame, it was just a one night stand.

Does it occur to you that all these guys have slept with this woman and now they’re sick? I have never heard someone say this is a poem about STD’s, but wow, it works. This girl is like the Typhoid Mary of love.

“Gloam’ is twilight. (No there are no freaking vampires around here. ) Again, we get symbolism about the end of life.

If the girl represents passionate disregard of scruples, Keats seems to be telling men that thinking a lusty woman loves you will haunt you till you die. he also implies that our natural desires are more powerful than any moral code we might try to follow.

Now women, don’t write this off as another sexist pig poem. Certainly, there are men who seduce and abandon naive women, but Keats isn’t required to look at all sides of an issue when he writes. He’s a guy, so he writes about how love can stink for men. That’s honesty.

Strangely enough, women novelists of this time period, Jane Austen and Emily Bronte’ for instance, often wrote about how love is nasty for both genders. (True, Charlotte Bronte’ showed that men can be insensitive. )It’s men, like Dickens and, later Hardy, who condemn the way women are treated. Now, in the last hundred or so years, women have more often had opportunity to tell their side of the story.

*I’d like to be abandoned in a forest with a passionate Bulgarian girl and see if I could understand her. Probably, I would understand the punches in the stomach she would fend me off with. (Have I gone too far, teachers?)